The state of education is in a maelstrom, and children, educators and families with it.

There's a pushmi-pullyu situation going on - it isn't new: Mary Jane Drummond sharply outlined this in her article 'Professional Amnesia - a suitable case for treatment' for the primary education magazine Forum in 2004. Pedagogy, provision and structures of education are being led by successive governmental drives and initiatives, which have for decades focussed primarily on concerns for economic growth and global competition. In amongst it all, education is conceived as largely a business of transmitting desired knowledge, and 'preparing for the next stage.' The language of 'achievement' and practices of assessment comes with this territory of 'value-adding.' 'Delivery', 'develop, 'attain', 'targets', 'milestones' are all words which have recent UK - especially English - official descriptors of early childhood (and later) education.

Not only the terminologies, but the organisation, habits and environments are also shaped by this discourse. England has one of the poorest minimal standards for educational environments in Europe – if knowledge transfer is the chief definer of desirable education then smaller spaces are adequate – children need to be uniform, passive, obedient and receptive. Programmes of rote-learning are commercial and are pushed as 'effective' and 'efficient.' The situation is diagnosed by many – Professor Peter Moss, Sir Ken Robinson and increasingly parents who have withdrawn their children from school.

We know that learners are not passive receptors. Children are born lively, curious, dynamic, sociable, expectant, creative – in Professor Colwyn Trevarthen's words 'humans (children) are born seeking relationship.' It follows that the education we construct, with the tools of time, organisation, space, professionalism should support this basic human zest, not constrain from the narrowing external concerns about 'upskilling tomorrow's workforce.' But it is a construct – and the lived reality of schools and early childhood centres is of course very nuanced, with many heads, staff groups, managers, committed to 'getting it right'. But it remains a muddle, and it is draining the natural energies of children, and of educators, and is a worry to many parents.

Not only the terminologies, but the organisation, habits and environments are also shaped by this discourse. England has one of the poorest minimal standards for educational environments in Europe – if knowledge transfer is the chief definer of desirable education then smaller spaces are adequate – children need to be uniform, passive, obedient and receptive. Programmes of rote-learning are commercial and are pushed as 'effective' and 'efficient.' The situation is diagnosed by many – Professor Peter Moss, Sir Ken Robinson and increasingly parents who have withdrawn their children from school.

We know that learners are not passive receptors. Children are born lively, curious, dynamic, sociable, expectant, creative – in Professor Colwyn Trevarthen's words 'humans (children) are born seeking relationship.' It follows that the education we construct, with the tools of time, organisation, space, professionalism should support this basic human zest, not constrain from the narrowing external concerns about 'upskilling tomorrow's workforce.' But it is a construct – and the lived reality of schools and early childhood centres is of course very nuanced, with many heads, staff groups, managers, committed to 'getting it right'. But it remains a muddle, and it is draining the natural energies of children, and of educators, and is a worry to many parents.

Let us be bold, open and incisive. There will be politicians who want to be led out of the deep hole that has been dug – we can see that in the examples from Italy, Portugal, Finland, Toronto for example, where educators and parents have articulated and led a vison of education focussed on empathy, sociability and enquiry. It does not begin with 'looking for measurable attainment outcomes'; it begins with amplifying and nurturing the possibilities of relationship and enquiry.This needs owners, managers, heads who will champion the construction of incisive, creative systems in which children can immerse themselves in enquiry. The construction of this relationship-rooted education expects educators to be listeners, researchers, co-constructors and proactive. Internationally speaking, UK early childhood educators are comparatively under-supported, under-qualified and under-paid. But all staff groups are able to become wonderful, researchful teams – we have seen this transformation as staff prioritise the setting as a place of relationships and find the courage and energy to ask good questions:

Sightlines Initiative: principles & characteristics for a relational pedagogy Our pre-schools, centres, schools can all be places of delight and research for children, for educators, families, communities. The aspirational journey can have a sound beginning in the fundamental enquiry – 'How do we learn to live well together?' It can't, I'm afraid, begin with drilling, rote-learning, or 'measuring milestones.'

Sightlines Initiative: principles & characteristics for a relational pedagogy Our pre-schools, centres, schools can all be places of delight and research for children, for educators, families, communities. The aspirational journey can have a sound beginning in the fundamental enquiry – 'How do we learn to live well together?' It can't, I'm afraid, begin with drilling, rote-learning, or 'measuring milestones.'

- What are ways in which we can resource and support children in enlivening their curiosity, confidence, daringness, absorption, questioning, exhilaration?

- What are ways we can find to bring these children together to discuss, agree and disagree? To engage in significant learning groups, delving into important ideas, experience and construction of knowledge?

- What are ways in which we can enable their sociable autonomy and rightful importance as citizens?

Sightlines Initiative: principles & characteristics for a relational pedagogy Our pre-schools, centres, schools can all be places of delight and research for children, for educators, families, communities. The aspirational journey can have a sound beginning in the fundamental enquiry – 'How do we learn to live well together?' It can't, I'm afraid, begin with drilling, rote-learning, or 'measuring milestones.'

Sightlines Initiative: principles & characteristics for a relational pedagogy Our pre-schools, centres, schools can all be places of delight and research for children, for educators, families, communities. The aspirational journey can have a sound beginning in the fundamental enquiry – 'How do we learn to live well together?' It can't, I'm afraid, begin with drilling, rote-learning, or 'measuring milestones.'

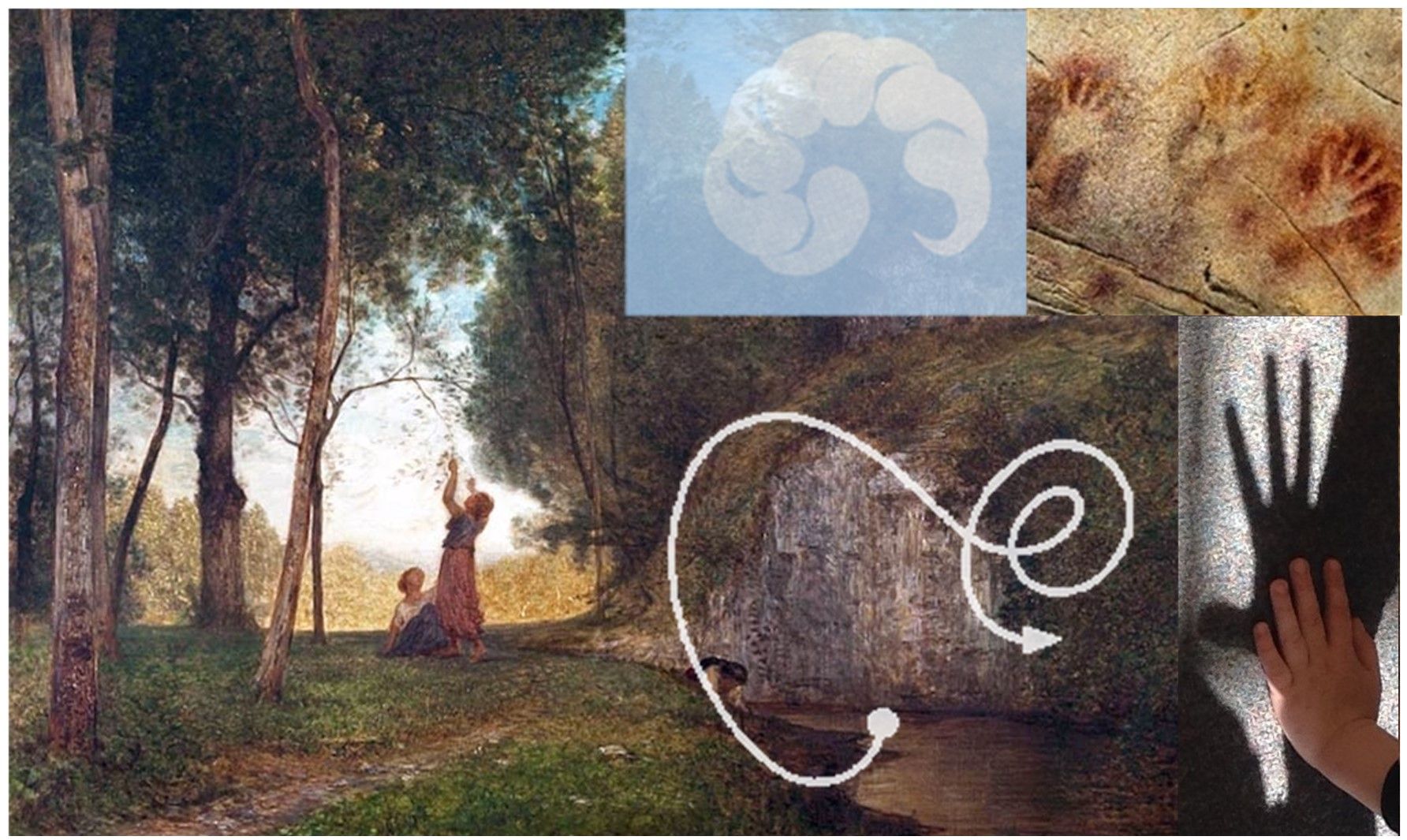

It can begin by considering more generously the ways in which humans learn, and engage with the world.

This is the aim of our summer series 'Learning to Live Well Together' of six internationally-renowned contributors, which begins on 6th July (we also have a complementary introductory session on the 29th June.)

This is the aim of our summer series 'Learning to Live Well Together' of six internationally-renowned contributors, which begins on 6th July (we also have a complementary introductory session on the 29th June.)

_(14566227128).jpg)